This new adaptation is sure to spark criticism from Döblin and Fassbinder loyalists, as well as those who might feel the film is not politically progressive enough. Nonetheless, it strikes the right chords: balancing between textual fidelity and contemporary relevance.

When Hollywood had the striking audacity to attempt to bring Nabakov’s celebrated novel to the big screen, the film’s poster asked the famous question, “How did they ever make a movie of Lolita?” (Of course, the answer was right there in the byline: they hired Stanley Kubrick to do it.)

One could easily ask the same question about Berlin Alexanderplatz, Alfred Döblin’s epic novel from 1929. For years, the book was considered to be untranslatable and — for many readers — incomprehensible, never mind unfilmable. The 500-page modernist masterpiece, written in the wild and heady atmosphere of the Weimar Era, is considered to be the German equivalent of Joyce’s Ulysses: dense yet playful, crude and funny, innovative and nonlinear, integrating stream-of-consciousness, multiple perspectives, experimental writing techniques, and even seemingly random excerpts — newspaper headlines, train schedules, and other montage sequences. In short: this is an all-encompassing wild ride of an epic, a trip better suited for a graduate seminar than a Sunday matinee.

Beyond this, against all odds, after 50 years the book did in fact become a film: a 15-hour tour de force period-drama masterminded by none other than Rainer Werner Fassbinder, the cocaine-and-amphetamine-fueled mad genius of the New German Cinema. (The film was originally released in 1980 as a miniseries for television, but is now typically regarded as a single work of art.) The sprawling project — and the energy needed to sustain this pace of production — may have been partially to blame for the director’s premature death just two years later, at the age of 37. The candle that burns twice as bright burns half as long. Since its initial release it has aged extremely well in the critical eye, now proclaimed as “the crowning achievement of a prolific director” by Criterion, following major efforts in 2007 to remaster, preserve, and rerelease the complete 902-minute work.

How, then, can one possibly make a — new — movie of Berlin Alexanderplatz? The answer, quite simply — as with Kubrick’s Lolita — is to approach the project with courage, boldness, and a fresh pair of eyes: to find a director willing to take what liberties are necessary to free the book from its history. An artist who will make it electric and relevant to viewers today, while still retaining the core and soul of the original work. Thus, whether you are a fan of the book, a Fassbinder cultist, or just a new recruit looking for a sizzling-hot new release to spark you out of your long COVID slumber, we strongly recommend you give some time to the latest adaptation, directed by Germany’s Burhan Qurbani.

The original book (and Fassbinder’s previous adaptation) follows the story of Franz Biberkopf (“Beaverhead”), an ex-con with a troubled past and a guilty conscience, who simply wants to be “a good man.” Unfortunately, the world has other plans for him: he falls in with a bad crowd (most notably a gangster named Reinhold), falls in love with a troubled woman (a prostitute named Mieze), makes some bad choices, and suffers a run of bad luck. We begin to recognize the inescapable fatalistic arc of tragedy etching itself onto the structure of a Bildungsroman.

In bringing his own vision of this classic story to the screen, Qurbani makes two important changes right from the outset. For starters, while the film is still long enough to deliver the requisite “epic experience” — three hours, broken down into five acts and an epilogue — it is significantly shorter than either the book or the miniseries, with fewer twists and turns and a smaller cast of characters. But while one might miss the full immersion provided by a longer format and meandering detours, the pacing is spot-on: rather than racing too quickly through a long checklist of plot points, the director allows the characters and their destinies to play out more slowly, often wordlessly, in natural time, with ample space for reflection, backpedaling, and the slow tightening of the knots of fate that are so characteristic of the story. This is a great example of how a slower cinema style may actually be more efficient than one chock full of rapid cuts, scene changes, roller-coaster sequences, or reams of rapid dialogue.

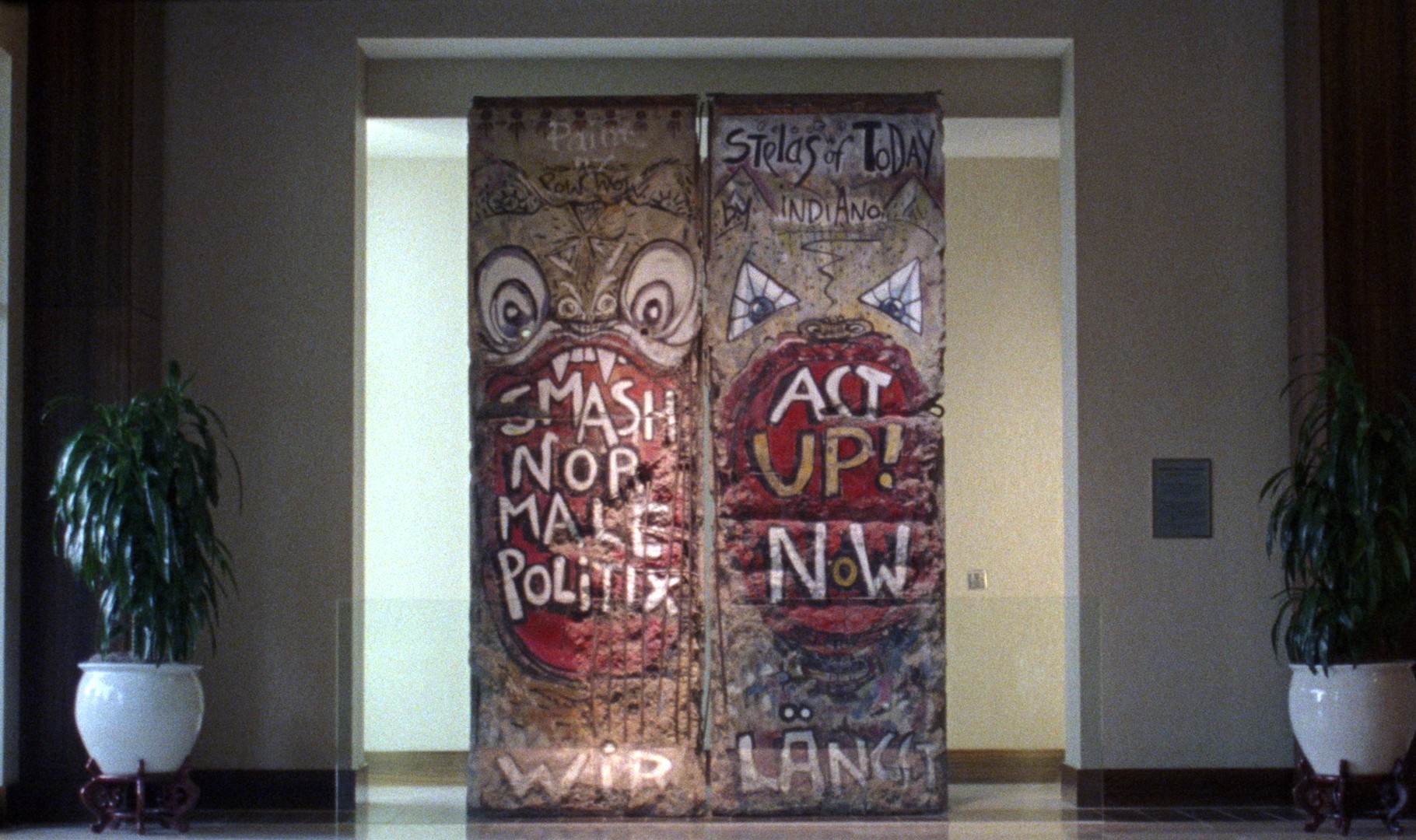

A second major shift — a departure from Fassbinder’s version — is to reset the tale for the present-day, Berlin, 2020. This decision reveals surprising similarities to the original Weimar setting: a world of chaos, intellectual tumult, financial insecurity, moral uncertainty, sexual liberation, chemical experimentation, a constant blurring of boundaries, and the pros and cons of a profound period of cultural reorientation. (In fact, stylistically, the film’s aesthetic seems to delight in a postmodern fusion of periods and fashions, combining elements from the ’20s reminiscent of Babylon Berlin, cool interior industrial design from the ’50s and ’60s, the out-and-open exuberant sexual pride of ’70s disco, and the funk-and-drone of present-day ecstasy-fueled techno-raves.) Albrecht Schuch and Welket Bungué in Berlin Alexanderplatz. Photo: Kino Lorber

But beyond simple matters of style, setting the story in 2020 allows for Qurbani’s most significant change, recasting Franz as “Francis” (Welket Bungué) an undocumented immigrant from Bissau who has made his way to Berlin. He’s lost the unlikely last name from the novel, but the character’s checkered past and honest, hopeful — and continually frustrated — desire to simply be good is all still there. The change is clever, thoughtful, and ultimately rewarding — far more than just a gimmick or a simple rewrite of the casting notes — and it opens up a world of new potential for the story. Franz’s original background, motives, and challenges still fit and have been retained. But the shift introduces new dynamics for Qurbani to explore — including the effects of pervasive racism and antimigrant sentiment, as well as the dual nature of fear and guilt experienced by undocumented immigrants, especially those who have fled the past and left something behind.

Thankfully, what has not been changed is the impressive scale, complexity, and depth of issues interwoven in the story’s achingly intractable setup. Crammed into every shot, scene, and exchange are a number of interconnected themes (and actions) driven by rage, jealousy, lust, and greed — really, all seven deadly sins. Other ills of the modern metropolis are not neglected: racism, misogyny, deceit, betrayal, fear, apathy, blame, shame, deviance, addiction, control, selfishness, vengeance, brutality, outright sadism, confusion, and even insanity. It’s truly amazing how much is packed in here: all bone, sinew, and muscle, with little excess fat.

In the heart-wrenching, tense middle acts we watch Francis fumble and stumble (and suffer) as he attempts to negotiate his allegiance to his psychopathic mentor Reinhold, played by Albrecht Schuch with a strangely charismatic blend of scheming menace, doting attentiveness, manic energy, and an undercurrent of fear and pain. (He looks eerily similar to the young Fassbinder). Francis is also struggling for a stable life with his new lover Mieze (Jella Haase), who takes him in. The woman brings much more to the table than the typical “hooker with a heart of gold,” combining strength and independence with a longing sadness and vulnerability. Francis struggles to keep his head above water, but there is little hope he will find a spot of solid ground under his feet, a life raft, or even a momentary pause to come up for air. We stand by, helpless, watching a web transform into net and then an ever-tightening straitjacket. Will the next step lead to a cell, a noose, or a coffin? (And Francis isn’t the only one ensnared: nearly everyone around him is trapped in one way or another. Often — poignantly — these entrapped characters are in turn twisting the reins on someone else’s bondage.)

Yet throughout — incredibly — like Francis, we find ourselves drawn to the irrepressible thrust of hope, wanting to defy the gravity of fate. The city is awash with obstacles and threats. But we still look for a sign of grace: for evidence of care, beauty, loyalty, love, honest connection, maybe even redemption — not from God, but from other broken humans who have learned from their shared painful experiences.

Visually, it’s a beautiful film, making excellent use of color, composition, and contrast. Every shot is well balanced, every frame is a photograph. In particular, Qurbani has perfected the art of capturing flesh tones — plural, the full range of them, often playing with the effects of color and light on the curves of shining radiant bodies, à la Barry Jenkins’s Moonlight. For example, his camera luxuriates on the intermingling of Bungué’s dark limbs and Haase’s pale torso. There’s a possibility that some may see this attention bleeding into questionable areas of exoticism and racialism, but these physical traits are so lovingly handled that the obsession is more refreshing than it is troubling. A similar fascination with our physical nature extends to depictions of eroticism — raising similar worries about the exploitation of sexuality. But again, the overall approach seems balanced, the female (and trans) characters are strong (albeit secondary), and this focus seems consistent with the libertine attitudes explored in the book. (That said, although I’m no prude, I could imagine an equally good edit of this film with only half as many thongs and pole-dancers.)

Lastly, concerning bodies and representation, the story relies heavily on themes of disfigurement and physical (as well as mental) disability, which may push the wrong buttons for some viewers, given changing attitudes since the Weimar days: do broken or twisted bodies necessarily translate to broken or twisted minds and souls?

In summation, while this new adaptation is sure to spark criticism from Döblin and Fassbinder loyalists, as well as those who might feel the film is not politically progressive enough, it nonetheless strikes the right chords: balancing between textual fidelity and contemporary relevance, Qurbani employs a fresh style and a bold approach to demonstrate that a 90-year-old story can be timeless, and still has a lot more to say.

(Note: this review also appeared in The Arts Fuse on 4/30/2021.)